The most popular SIBO diets pros and cons PART 1

If you are diagnosed with SIBO (Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth), you must have been advised to follow a "SIBO diet" for a while (hopefully, not forever!).

What is SIBO?

SIBO stands for Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth and is defined as the presence of excessive bacteria in the small intestine. Bacteria start fermenting carbohydrates, starches, and fibers and produce gases, which can cause damage to the small intestines' wall and lead to various symptoms. (1)

These symptoms could be bloating and gas, diarrhea and/or constipation, abdominal pain, nausea, belching, reflux, rashes, food intolerances, and many more. The whole process would be expected if it occurred in the large intestine, where it is supposed to happen. (2)

SIBO is categorized into different subtypes:

- Hydrogen

- Methane (technically not a bacteria, but archaea)

- Hydrogen sulfide

The main difference between these three types of SIBO is the gases produced by the bacteria or other organisms residing in the small bowel. It is also possible that someone has a mixed type of SIBO, meaning multiple types of gases are present simultaneously. (3)

To get diagnosed with SIBO, you need to do a 3-hour lactulose/glucose breath test.

What are SIBO diets?

Many practitioners recommend a SIBO diet as an additional tool next to antibiotics or antimicrobial treatment for SIBO.

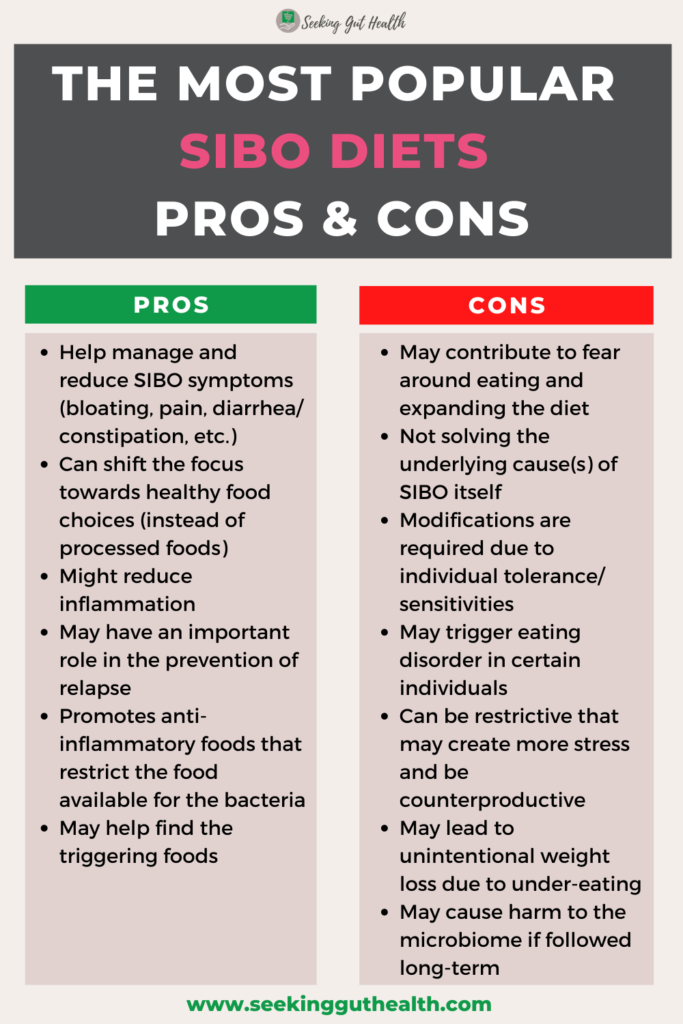

SIBO diets aim to decrease the number of fermentable carbohydrates in your diet. These diets may help you:

- relieve uncomfortable or extreme symptoms of gassiness, bloating, diarrhea,

- reduce "die-off symptoms" during a treatment,

- reduce inflammation,

- prevent a possible relapse after treatment.

These fermentable carbohydrates serve as food for the bacteria. Each diet removes/allows specific carbohydrates to address carbohydrate malabsorption issues.

The following diets are mainly used as a SIBO diet:

- Elemental diet,

- Low-FODMAP diet,

- Specific Carbohydrate Diet (SCD),

- The SIBO Specific Food Guide (SSFG),

- Cedars-Sinai low fermentation diet,

- Bi-phasic diet,

- Alternatively, GAPS, Fast Tract, Paleo, and Ketogenic diet.

It is important to note that currently, there is no evidence that these diets alone can eliminate overgrowth, except the Elemental diet.

Some practitioners have more of a liberal dietary approach based on the client's situation, meaning they don't restrict the intake of fermentable carbohydrates that much. The reason is that they believe that bacteria may form and hide behind biofilms. This protective layer saves bacteria from the effect of antimicrobials or antibiotics, making them resistant to the treatment. Feeding the bacteria may prevent that they hide behind biofilms. (4)

Let's look at these diets one by one:

SIBO diet #1: Elemental diet

An Elemental diet is the only exception in terms of using a diet as a treatment option. This diet is one of the most restrictive diets as you are not allowed to eat any solid food for 2-3 weeks. But this is not the same as fasting!

An Elemental diet is considered to be a medical food beverage, a liquid formula composed of proteins (as amino acids), fats (as medium-chain triglycerides), carbohydrates (as glucose or maltodextrin without any fiber), vitamins, and minerals that can be used for symptom management and treatment. (5)

It can help

- starve the bacteria as nutrients are absorbed before bacteria has a chance to feed on

- your body get nourished with the pre-digested formula

- when you have malabsorption issues

- give the digestive system a break from digestion, so it has finally an opportunity to heal

What does the research say? A 14-day long Elemental Diet has been found to have an 80% success rate in SIBO treatment by normalizing the breath test. (6) So it seems to be highly effective.

What are the Pros?

- As the research says, it is highly effective to treat SIBO

- The treatment duration is relatively short (2-3 weeks) comparing to other diets or treatments

- It is still considered a natural approach that many people like

- It can help relieve symptoms and improve GI functions

- It can be beneficial for clients who failed other treatment options in the past

- For those who don't want to be bothered with cooking

What are the Cons?

- It can be expensive if it is purchased from a company/brand

- Homemade elemental diets can be a bit challenging to assemble

- It usually has an unpleasant taste

- Emotionally challenging as no solid food can be eaten for 2-3 weeks (no eating out)

- There is a risk for weight loss if the daily calorie is not reached

- It may be high in carbohydrates that not ideal for diabetic clients

- It has to be used cautiously if a fungal overgrowth is suspected

In my opinion, this shouldn't be the first line of treatment but rather the last when all other treatment options have failed. It is best to be used under a Practitioner's supervision.

You can find more information about the Elemental diet on Dr. Siebecker's website.

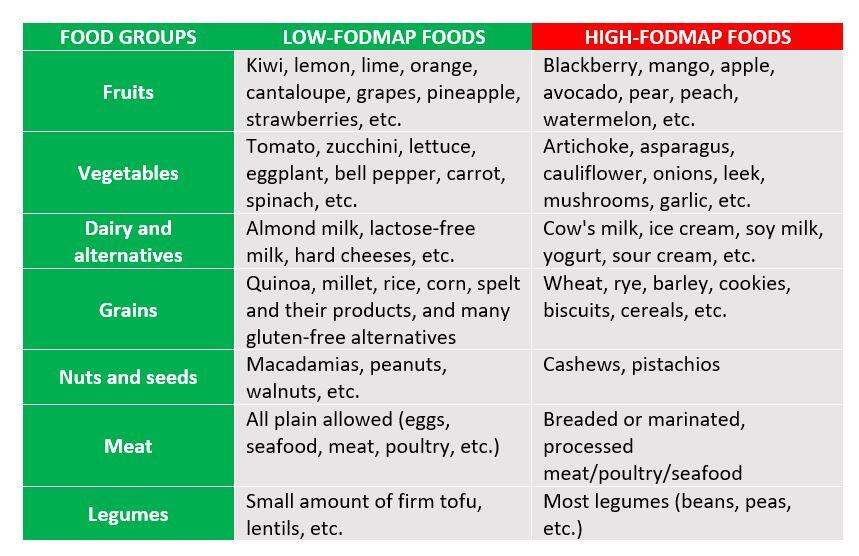

SIBO diet#2: Low-FODMAP diet

The Low-FODMAP diet is another popular dietary approach that is commonly used among IBS and SIBO patients. It was created by the Monash University (in Australia) for IBS (Irritable Bowel Syndrome) symptom management.

FODMAP is an acronym for "Fermentable Oligo-, Di-, Mono-saccharides And Polyols." (7) These are short-chain carbohydrates and sugar alcohols that are poorly absorbed in the body. The bacteria ferment these carbohydrates and create gases, resulting in abdominal pain and bloating.

It includes:

- oligosaccharides, including fructans and galactooligosaccharides

- disaccharides, including lactose

- monosaccharides, including fructose

- polyols, including sorbitol, xylitol, and mannitol.

A low-FODMAP diet is recommended for patients with IBS to help reduce digestive symptoms of IBS, including bloating, flatulence, and diarrhea. According to clinical trials, the diet effectively improves symptoms in up to 70% of IBS patients. (8)(9)

A low-FODMAP diet is used for 2 to 6 weeks as an elimination diet to remove foods considered high FODMAP to find out whether these foods are causing a problem for the person with a digestive disorder like IBS to relieve symptoms. Then a reintroduction and a personalization phase should follow.

Here is a brief overview of the low and high-FODMAP-containing foods:

You can find the exact information about the FODMAP content of foods on Monash University's app.

So, I mentioned that this diet is beneficial for people with IBS, but how about SIBO? Well, there is a connection between IBS and SIBO. Research showed that up to 78% of patients with IBS have SIBO. (10) This explains why the low FODMAP diet is often utilized for SIBO patients, especially when symptoms are identical to IBS.

What are the Pros?

- Useful for symptom management in clients with IBS (11)

- It helps reduce IBS symptoms in patients with IBD (Inflammatory Bowel Disease) (12)

- There is tons of information and an official app that can help with shopping, meal planning, cooking

- It is less restrictive than other SIBO diets

- It can help identify possible triggers

What are the Cons?

- A long-term low-FODMAP diet may have a negative effect on the gut microbiome (as fructans and galacto-oligosaccharides have prebiotic properties – they can feed the good gut bacteria, long-term avoidance of these can lead to the decrease of beneficial bacteria in the colon) (13)

- Possible nutrient deficiencies if the diet is not well-designed

- Many people develop food fears and get stuck in the elimination phase for too long, contributing to disordered eating

- Sticking to the framework can be challenging

- It can have a negative impact on social events (including eating out)

Many people see improvement in their IBS & SIBO symptoms with the low-FODMAP diet, but some will not see 100% symptom improvement. So, it is good to keep in mind that this is happening because food is not the only factor that affects the gut.

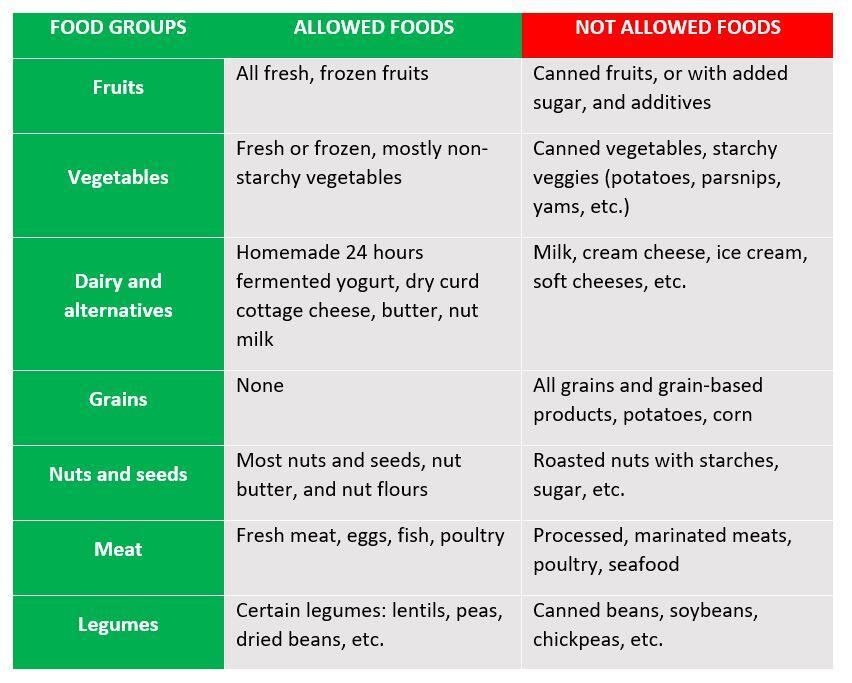

SIBO diet#3: Specific Carbohydrate Diet (SCD)

The Specific Carbohydrate Diet (SCD) is a typical elimination diet that restricts complex carbohydrates, completely eliminating grains. The diet allows monosaccharides but excludes disaccharides and most polysaccharides, which might feed the bacteria without proper absorption and digestive function (enzyme production), resulting in inflammation and digestive symptoms. Removing troublesome carbohydrates may help lower gas production, inflammation, and gut permeability.

Dr. Sidney Haas developed the SCD diet to treat patients with celiac disease, then later Elaine Gottschall published her book "Breaking the Vicious Cycle," and the diet became popular and successfully used for Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) such as Ulcerative Colitis, Crohn disease. (14)

Here is a brief overview of the allowed and not allowed foods on the SCD diet:

You can find detailed information about the complete list of allowed foods and implementation stages in Elaine Gottschall's book "Breaking the Vicious Cycle."

What are the Pros?

- It can help reduce the digestive symptoms (especially in IBD controlling acute flare and maintaining remission) by reducing fermentation in the gut (15)

- Decrease inflammation (16)

- It can positively influence the microbiome and decrease dysbiosis (17)

- It can reduce the need for medications (in IBD patients) (14)

What are the Cons?

- It is a very restricted diet

- Possible nutrient deficiencies if the diet is not designed well (whole food groups are removed)

- It requires a lot of preparation, meal planning, cooking

- It can have a negative impact on social events

What is the relationship with SIBO? There is currently no research proving that the SCD diet is efficient for SIBO, but it certainly may have the potential to help with inflammation and limit the food for bacteria. Therefore, the SCD diet is commonly used among SIBO patients as it removes the complex carbs that bacteria commonly feed on in the small bowel. It can also be helpful for people with a deficiency of carbohydrate enzymes.

In many cases, practitioners combine the SCD diet with the low-FODMAP diet.

The Bottom Line

Whatever diet you may choose, it is essential to know that everyone has a unique mixture of bacterial species that makes food tolerance varied, so diet modification is always required.

A SIBO diet should be followed for no more than a few months. Long-term usage may deplete the beneficial bacteria in the gut, causing more harm than good (especially in the case of the low-FODMAP diet).

These therapeutic diets are meant to help you reduce inflammation and symptoms in a short period. After an elimination phase, a reintroduction phase should follow when you add back foods one at a time and check for any symptoms.

I have also met clients stuck in the elimination phase for too long due to food fear. They saw the nutritious foods as their enemies! That is a dangerous pathway as this might interfere with their recovery process.

Once you have identified your worst triggers, the long-term goal should be to extend your diet as much as possible.

However, the ultimate focus during a SIBO treatment should be on finding the underlying causes that contribute to SIBO.

Check out my next blog post about the other popular SIBO diets, where I reviewed the pros and cons of the SIBO Specific Food Guide (SSFG), the SIBO Bi-phasic diet, the Cedars-Sinai diet low fermentation diet, and the Fast Tract Diet.

This post is only for informational purposes and is not meant to diagnose, treat, or cure any disease. I recommend consulting with your healthcare practitioner always before trying any treatment or dietary changes.

Dukowicz, A. C., Lacy, B. E., & Levine, G. M. (2007). Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth: a comprehensive review. Gastroenterology & hepatology, 3(2), 112–122.

Bures, J., Cyrany, J., Kohoutova, D., Förstl, M., Rejchrt, S., Kvetina, J., Vorisek, V., & Kopacova, M. (2010). Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth syndrome. World journal of gastroenterology, 16(24), 2978–2990. doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v16.i24.2978

Sorathia SJ, Rivas JM. Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth. [Updated 2021 Jul 18]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK546634/

López, D., Vlamakis, H., & Kolter, R. (2010). Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology, 2(7), a000398. https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a000398

Alexander, D. D., Bylsma, L. C., Elkayam, L., & Nguyen, D. L. (2016). Nutritional and health benefits of semi-elemental diets: A comprehensive summary of the literature. World journal of gastrointestinal pharmacology and therapeutics, 7(2), 306–319. https://doi.org/10.4292/wjgpt.v7.i2.306

Pimentel, M., Constantino, T., Kong, Y., Bajwa, M., Rezaei, A., & Park, S. (2004). A 14-day elemental diet is highly effective in normalizing the lactulose breath test. Digestive diseases and sciences, 49(1), 73–77. https://doi.org/10.1023/b:ddas.0000011605.43979.e1

Schumann, D., Klose, P., Lauche, R., Dobos, G., Langhorst, J., & Cramer, H. (2018). Low fermentable, oligo-, di-, mono-saccharides and polyol diet in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrition (Burbank, Los Angeles County, Calif.), 45, 24–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nut.2017.07.004

Staudacher, H. M., & Whelan, K. (2017). The low FODMAP diet: recent advances in understanding its mechanisms and efficacy in IBS. Gut, 66(8), 1517–1527. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2017-313750

Mohannad Dugum, MD, Kathy Barco, RD, LD, CNSC and Samita Garg, MD, Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine September 2016, 83 (9) 655-662; DOI: https://doi.org/10.3949/ccjm.83a.14159

Ghoshal, U. C., Shukla, R., & Ghoshal, U. (2017). Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth and Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Bridge between Functional Organic Dichotomy. Gut and liver, 11(2), 196–208. https://doi.org/10.5009/gnl16126

Altobelli, E., Del Negro, V., Angeletti, P. M., & Latella, G. (2017). Low-FODMAP Diet Improves Irritable Bowel Syndrome Symptoms: A Meta-Analysis. Nutrients, 9(9), 940. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9090940

Pedersen, N., Ankersen, D. V., Felding, M., Wachmann, H., Végh, Z., Molzen, L., Burisch, J., Andersen, J. R., & Munkholm, P. (2017). Low-FODMAP diet reduces irritable bowel symptoms in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. World journal of gastroenterology, 23(18), 3356–3366. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i18.3356

Hill, P., Muir, J. G., & Gibson, P. R. (2017). Controversies and Recent Developments of the Low-FODMAP Diet. Gastroenterology & hepatology, 13(1), 36–45.

Suskind, D. L., Wahbeh, G., Gregory, N., Vendettuoli, H., & Christie, D. (2014). Nutritional therapy in pediatric Crohn disease: the specific carbohydrate diet. Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition, 58(1), 87–91. https://doi.org/10.1097/MPG.0000000000000103

Kakodkar, S., Farooqui, A.J.,Mikolaitis,S.L., Mutlu, E.A. (2015). The Specific Carbohydrate Diet for Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Case Series. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 115 (8), 1226-1232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2015.04.016

Olendzki, B. C., Silverstein, T. D., Persuitte, G. M., Ma, Y., Baldwin, K. R., & Cave, D. (2014). An anti-inflammatory diet as treatment for inflammatory bowel disease: a case series report. Nutrition journal, 13, 5. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2891-13-5

Suskind, D. L., Cohen, S. A., Brittnacher, M. J., Wahbeh, G., Lee, D., Shaffer, M. L., Braly, K., Hayden, H. S., Klein, J., Gold, B., Giefer, M., Stallworth, A., & Miller, S. I. (2018). Clinical and Fecal Microbial Changes With Diet Therapy in Active Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Journal of clinical gastroenterology, 52(2), 155–163. https://doi.org/10.1097/MCG.0000000000000772

The most popular SIBO diets pros and cons PART 1 Read More »